William

Walker had a dream, a dream shared by many pro-slavery advocates in the

ante-bellum South. Walker’s dream involved the expansion of slavery into Latin

America. Known as “filibustering,” the idea was not a new one, but the young

and energetic Walker actually worked to implement it.

William

Walker (1824-1860) was born in Nashville, Tennessee, the son of a Scottish

immigrant. After graduating from the University of Nashville at the top of his

class (at age fourteen), Walker (right) went to Europe to study medicine. Returning to

the United States, he continued his studies in Philadelphia, where he obtained

a degree at age nineteen and practiced medicine for a short time. Moving south

to New Orleans in 1845, he became a lawyer and a newspaper editor. In 1850, after

his deaf-mute fiancée died, he moved to San Francisco.

In

California, Walker was a newspaper man and, when not fighting duels, got

involved in the Manifest Destiny movement. It was then that Walker seized upon the idea

of conquering Latin America and turning the whole region into a slavocracy.

This slaveholding empire encircling the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean

states, including Cuba, was sometimes referred to as “the golden circle.” In 1853, Walker traveled to Mexico to try and

convince the government there to give him a grant to establish a colony on the

border between Mexico and the United States. Not surprisingly, Mexican

officials refused. Not deterred, Walker made plans to raise his own army to

take land from Mexico and establish the “Republic of Sonora,” funded by the

sale of bonds, or “scrips,” only redeemable in (you guessed it) the “Republic

of Sonora.”

In

October, Walker and forty-five men landed in sparsely-populated Baja,

California, captured the capital, and declared it the capital of the

“Republic of Lower California,” with Walker as president. When he was unable to

actually go into Sonora as planned, Walker simply declared that Baja was part

of a larger “Republic of Sonora.” Not surprisingly, he was soon ousted by the

Mexican government. Back home in California, U.S. officials put him on trial

for starting an illegal war. The jury, however, acquitted him in just eight

minutes.

Still looking to establish himself

somewhere in Latin America, Walker found a sympathetic benefactor in Nicaragua,

which was at the time caught up in a civil war between political parties. To

help combat their rivals in the Legitimist Party, the Democratic Party called

for help from Walker. Nicaraguan president Francisco Castellon Sanabria (right), a

member of the Democratic faction, invited Walker to bring up to three hundred “colonists”

to Nicaragua and gave them the right to bear arms. Technically, therefore, they

were invited guests. In reality, Walker now had the freedom to act as a

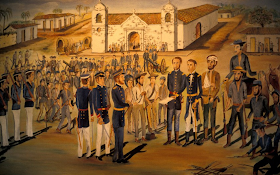

mercenary (the image above shows some of his rag-tag volunteers). Sailing from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with sixty men (far short

of the 300 allowed), Walker landed in Nicaragua and was joined there by almost

three hundred locals and Americans.

Still looking to establish himself

somewhere in Latin America, Walker found a sympathetic benefactor in Nicaragua,

which was at the time caught up in a civil war between political parties. To

help combat their rivals in the Legitimist Party, the Democratic Party called

for help from Walker. Nicaraguan president Francisco Castellon Sanabria (right), a

member of the Democratic faction, invited Walker to bring up to three hundred “colonists”

to Nicaragua and gave them the right to bear arms. Technically, therefore, they

were invited guests. In reality, Walker now had the freedom to act as a

mercenary (the image above shows some of his rag-tag volunteers). Sailing from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with sixty men (far short

of the 300 allowed), Walker landed in Nicaragua and was joined there by almost

three hundred locals and Americans.  Walker immediately attacked the

Legitimist town of Rivas. Although his first attack failed, Walker’s little

army defeated the Legitimist forces on September 4 and on October 13 captured

the opposition capital of Granada. Having accomplished the task of knocking out

the opposition party, Walker became the de

facto ruler of Nicaragua after Francisco Castellon died. Walker’s regime

was recognized by U.S. government in 1856, during the Franklin Pierce

administration. American recognition was soon withdrawn, however, when Walker

conspired to seize the Accessory Transit Company, owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt

(the company controlled the route across Central America prior to the Panama

Canal). Vanderbilt, infuriated by Walker’s hostile takeover, convinced Pierce

to withdraw recognition. At the same time, Walker’s neighbors in Central

America grew increasingly alarmed at rumors of more invasions by Walker’s men. To

combat the growing threat, Honduras, Costa Rica and Guatemala formed a

coalition army, with arms supplied by the British government and financial

backing from Commodore Vanderbilt. In 1856, Costa Rica and Honduras declared

war on Nicaragua.

Walker immediately attacked the

Legitimist town of Rivas. Although his first attack failed, Walker’s little

army defeated the Legitimist forces on September 4 and on October 13 captured

the opposition capital of Granada. Having accomplished the task of knocking out

the opposition party, Walker became the de

facto ruler of Nicaragua after Francisco Castellon died. Walker’s regime

was recognized by U.S. government in 1856, during the Franklin Pierce

administration. American recognition was soon withdrawn, however, when Walker

conspired to seize the Accessory Transit Company, owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt

(the company controlled the route across Central America prior to the Panama

Canal). Vanderbilt, infuriated by Walker’s hostile takeover, convinced Pierce

to withdraw recognition. At the same time, Walker’s neighbors in Central

America grew increasingly alarmed at rumors of more invasions by Walker’s men. To

combat the growing threat, Honduras, Costa Rica and Guatemala formed a

coalition army, with arms supplied by the British government and financial

backing from Commodore Vanderbilt. In 1856, Costa Rica and Honduras declared

war on Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, Walker went about installing himself as President

after conducting a sham election. Inaugurated on July 12, Walker immediately

reestablished slavery (outlawed by Nicaragua in the 1820s), made English the

official language and changed the currency and banking system to be more in

keeping with the Southern U.S. states, hoping to attract investors.

Although there was some

interest in the new republic from Southerners, the experiment lasted less than

a year. By December 14, 1856, Granada was surrounded by the coalition army. Rather

than risk capture, one of Walker’s generals decided it would be best to burn

the city and fight their way out. They did so, and left the city in ruins,

concentrating their forces in the city of Rivas. For five months, his army held

out against superior forces. Finally, on May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to a

U.S. naval officer, who negotiated the surrender of the city (right) and then shipped Walker back

to the United States.

Although there was some

interest in the new republic from Southerners, the experiment lasted less than

a year. By December 14, 1856, Granada was surrounded by the coalition army. Rather

than risk capture, one of Walker’s generals decided it would be best to burn

the city and fight their way out. They did so, and left the city in ruins,

concentrating their forces in the city of Rivas. For five months, his army held

out against superior forces. Finally, on May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to a

U.S. naval officer, who negotiated the surrender of the city (right) and then shipped Walker back

to the United States.

Back home, many people considered Walker

to be a hero, and he considered himself the legitimate president of Nicaragua.

As such, he toured the South to try to raise funds to retake Nicaragua. In

Mississippi, as elsewhere, his public appearances created a lot of sympathy and

excitement. In a November 1860 Natchez newspaper, the editor

predicted with great anticipation the creation of a slaveholding empire along

the Gulf of Mexico, which would become, the newspaper wrote, “simply a Southern

lake, to be whitened with thousands of Southern sails.” Walker tried several

times to return to Nicaragua, but was foiled in each attempt.

In 1860, British colonists in the Bay

Islands (off the coast of Honduras) approached Walker about establishing an independent,

English-speaking government (they were fearful of the Hondurans). Never one to

pass up an opportunity, Walker agreed and boarded a ship, arriving in the port

city of Trujillo. This time, he was captured by the British Navy, which

regarded anyone intending to upset the region’s political balance to be

dangerous. Instead of being shipped back

to the United States, Walker was delivered to Honduran authorities, and Walker

was summarily executed by firing squad on September 12, 1860 (above). After all this,

he was still just 36 years old. He is buried in Trujillo (his grave is seen at right). Because of the Walker

incident, the British gave the Bay Islands to the Honduran government. Thus ends the story of William Walker.

In 1860, British colonists in the Bay

Islands (off the coast of Honduras) approached Walker about establishing an independent,

English-speaking government (they were fearful of the Hondurans). Never one to

pass up an opportunity, Walker agreed and boarded a ship, arriving in the port

city of Trujillo. This time, he was captured by the British Navy, which

regarded anyone intending to upset the region’s political balance to be

dangerous. Instead of being shipped back

to the United States, Walker was delivered to Honduran authorities, and Walker

was summarily executed by firing squad on September 12, 1860 (above). After all this,

he was still just 36 years old. He is buried in Trujillo (his grave is seen at right). Because of the Walker

incident, the British gave the Bay Islands to the Honduran government. Thus ends the story of William Walker. Although Walker failed to make

his dream come true, his daring made him a popular figure in the South, where

he was known as “General Walker” and the “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny.” In Central

America, however, the military

campaign to oust him is a point of pride for Central American independence. In

fact, there is a national holiday in Costa Rica (on April 11) to celebrate the

victory against Walker at Rivas and the bravery of Juan Santamaria, Costa Rica's greatest national hero (his monument is seen here). A drummer boy, Santamaria volunteered to advance across open ground in order to torch a stronghold held by Walker's men during the battle of Second Rivas. Although he was killed by a sniper, Santamaria successfully applied the torch and helped win the battle for the Costa Rican army. Whether this is factual or not is of secondary importance; today, Juan Santamaria is a national hero akin to those of the American Revolution in the U.S. On the other side of the ledger, William Walker's reputation in the

region is infamous, and he is still remembered with great scorn. His reputation is so toxic that when a U.S. Ambassador was appointed to El Salvador in 1988, it

caused a wave of consternation in Latin America. The ambassador's name? William G.

Walker.

Although Walker failed to make

his dream come true, his daring made him a popular figure in the South, where

he was known as “General Walker” and the “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny.” In Central

America, however, the military

campaign to oust him is a point of pride for Central American independence. In

fact, there is a national holiday in Costa Rica (on April 11) to celebrate the

victory against Walker at Rivas and the bravery of Juan Santamaria, Costa Rica's greatest national hero (his monument is seen here). A drummer boy, Santamaria volunteered to advance across open ground in order to torch a stronghold held by Walker's men during the battle of Second Rivas. Although he was killed by a sniper, Santamaria successfully applied the torch and helped win the battle for the Costa Rican army. Whether this is factual or not is of secondary importance; today, Juan Santamaria is a national hero akin to those of the American Revolution in the U.S. On the other side of the ledger, William Walker's reputation in the

region is infamous, and he is still remembered with great scorn. His reputation is so toxic that when a U.S. Ambassador was appointed to El Salvador in 1988, it

caused a wave of consternation in Latin America. The ambassador's name? William G.

Walker. PHOTO AND IMAGE SOURCES:

(1) Walker: http://en.wikipedia.org

(2) Walker's army: http://historymatters.gmu.edu

(3) Francisco Castellon: http://www.mined.gob.ni/gobern12.php

(4) Map: http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/exhibits/walker/index.htm

(5) Surrender: http://johnsmitchell.photoshelter.com

(4) Map: http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/exhibits/walker/index.htm

(5) Surrender: http://johnsmitchell.photoshelter.com

(6) Walker execution: http://www.bookdrum.com

(7) Walker grave: http://www.latinamericanstudies.org

(8) Monument: http://costaricasunshine.com/en/cultural-activities

(7) Walker grave: http://www.latinamericanstudies.org

(8) Monument: http://costaricasunshine.com/en/cultural-activities

Very interesting. Thanks.

ReplyDelete