During World War I, Payne Field, located about four miles

north of West Point, Mississippi, was used as a training facility for military

pilots. Consisting of 533 acres and constructed at a cost of $891,340, Payne

Field was the first airfield in Mississippi. During the period the facility was

active (May 1918-March 1920), approximately 1,500 pilots were trained for

service overseas with 125 Curtiss JN-4 airplanes. Known as the “Jenny,” the

JN-4 was one of a series of biplanes built by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company of

New York. During the war, the planes were widely used as training aircraft for

the U.S. Army, and in the 1920s, after being sold off as surplus, became a

mainstay of civilian aviation. Payne Field was named in memory of Capt.

Dewitt Payne. A native of South Bend, Indiana, Payne graduated from the

University of Michigan in 1912 and the School of Military Aeronautics at the

University of Illinois, where he was commissioned as a First Lieutenant and

sent to a training field in Long Island, New York. Promoted to captain in

October, 1917, Payne was transferred to an airfield in Texas. There, on

February 1, 1918, Payne was flying to the aid of a pilot who had crashed into

the top of a tree and crashed his own plane in the process. He died from the injuries sustained in the

crash. The year following his death, the

University of Michigan yearbook noted that the naming of the airfield in West

Point, Mississippi, was “a fitting testimony of the esteem in which he was held

as man, soldier, and flier.”

The commander of Payne Field was Lt. Col. Jack W. Heard.

Heard (right) was a career army officer, a West Point graduate (class of 1910), and the

son of Medal of Honor John W. Heard, a native of Woodstock, Mississippi. His

father (Jack’s grandfather) fought in a Mississippi cavalry unit with Nathan

Bedford Forrest during the Civil War, so Col. Heard’s roots both in the army

and in Mississippi were deep. After

graduation from West Point, Heard was assigned to the 7th Cavalry

(George Custer’s old regiment) and was sent to the Philippines. It was here

that Heard first became interested in the new phenomenon of flying, and after

several applications for transfer he was finally approved for the Aviation

Section of the Signal Corps and earned his pilot’s certificate. Quickly rising

in the ranks of the Air Corps, he went on to command three training bases

during the First World War: Kelly Field in Texas, Scott Field in Illinois, and

Payne Field.

The commander of Payne Field was Lt. Col. Jack W. Heard.

Heard (right) was a career army officer, a West Point graduate (class of 1910), and the

son of Medal of Honor John W. Heard, a native of Woodstock, Mississippi. His

father (Jack’s grandfather) fought in a Mississippi cavalry unit with Nathan

Bedford Forrest during the Civil War, so Col. Heard’s roots both in the army

and in Mississippi were deep. After

graduation from West Point, Heard was assigned to the 7th Cavalry

(George Custer’s old regiment) and was sent to the Philippines. It was here

that Heard first became interested in the new phenomenon of flying, and after

several applications for transfer he was finally approved for the Aviation

Section of the Signal Corps and earned his pilot’s certificate. Quickly rising

in the ranks of the Air Corps, he went on to command three training bases

during the First World War: Kelly Field in Texas, Scott Field in Illinois, and

Payne Field.

As training commenced at Payne Field, several fatal

accidents occurred, four within the first few months after the base was

established. Among the casualties was a young flier named Clarke Owen of

Lansing, Michigan, whose plane crashed from a height of 100 feet near Muldon (located

in Monroe County). A companion was also

seriously injured in the crash. As dangerous as flying was, disease was also a

great concern for the men at Payne Field. In June, 1918, the U.S. Public Health

Service reported that the airfield was located in “one of the worst malaria

belts of the United States” and that local physicians claimed that 75% of the

region’s population were infected with the disease. It was pneumonia, however, which claimed the

life of James Madison Allen (left), a member of the 239th Aero Squadron. The

thirty-year-old sergeant died on January 31, 1919, in the hospital at Camp

Shelby, where he had been sent to recover. He is buried in the Woodlawn

Cemetery in Sharon, Tennessee.

As training commenced at Payne Field, several fatal

accidents occurred, four within the first few months after the base was

established. Among the casualties was a young flier named Clarke Owen of

Lansing, Michigan, whose plane crashed from a height of 100 feet near Muldon (located

in Monroe County). A companion was also

seriously injured in the crash. As dangerous as flying was, disease was also a

great concern for the men at Payne Field. In June, 1918, the U.S. Public Health

Service reported that the airfield was located in “one of the worst malaria

belts of the United States” and that local physicians claimed that 75% of the

region’s population were infected with the disease. It was pneumonia, however, which claimed the

life of James Madison Allen (left), a member of the 239th Aero Squadron. The

thirty-year-old sergeant died on January 31, 1919, in the hospital at Camp

Shelby, where he had been sent to recover. He is buried in the Woodlawn

Cemetery in Sharon, Tennessee.

All was not death and disease at Payne Field, however. In

September, 1918, Colonel Heard received a delightful letter from a young man in

Okolona, Mississippi, with an unusual request. The boy’s letter, and Col.

Heard’s poignant response, is reprinted here as it appeared in the New York

Times on September 15, 1918:

A LETTER FROM THE AIR.

From a C.O. to a Boy Who Could Not Be a Soldier.

To the Editor of the New York Times:

Attached, I am forwarding you a copy of a letter received

by the commanding officer of this field from a little boy, 12 years old, living

in a town north of here, over which our airplanes fly very frequently. The

letter is so fine and cheerful and so full of courage and inspiration that you

may wish to publish it. If a little boy, handicapped as he is, can maintain

such a bright outlook upon life, the knowledge of that fact and the spirit of

the letter should encourage those who may be tempted to complain in these

trying times.

J.S. Schulussel

First Lieutenant, A.S.S.C.

Headquarters Air Service Flying School, Payne Field, West

Point, Miss., Sept. 5, 1918

_____

[Inclosure]

[Inclosure]

Okolona, Miss., September 3, 1918.

Dear Colonel Heard:

I just want to write and tell you how much I enjoy your aviators.

I am a paralyzed cripple boy and don’t have very much pleasure, but your fliers

and their wonderful stunts give me more pleasure than anything in my life. I

can sit in our front yard and see them all day. Won’t you please ask them to do

all their wonders right where I can see them? I live in South Okolona in a

two-story bungalow due south of the Baptist Church, and if they will fly

straight north up that long road and street south of the Baptist Church my

mamma has a twenty-acre field right by our house, and I don’t think she will

care if they will light right in the corn. And, last, won’t you or your

aviators drop me a letter in our yard some time? I have two brothers already in

France and three more to go in the next draft but I will never be able to do

anything but wave at you all and yell hurrah for Uncle Sam. I hope I haven’t

troubled you by writing and pardon pencil, but I’m too shaky to use a pen.

Love to you and all your aviators from WARDIE G. DAWSON.

P.S. – I’m going to watch for letter to fall to me from

now on. W.G.D.

______

Headquarters Air Service Flying School, Payne Field,

West

Point, Miss.

Sept. 4, 1918.

Sept. 4, 1918.

From the Commanding Officer.

To Wardie G. Dawson, Okolona, Miss.

Subject: Delivery of letter by airplane.

1. Your letter, my

dear little friend, afforded me a great deal of pleasure, and I am glad to be

able to oblige a fine young American like you, who has not the strength and

health to be a soldier. You must not let your condition discourage you, for it

is not only those who bear arms who will do their part in winning the war and

achieving victory for freedom. Those who accept hardships with fortitude and

can radiate happiness in spite of misfortune are the bravest sort of people,

and it is brave men and women and boys and girls who have made our country what

it is and who are going to keep it so.

2. I am glad to know that our fliers and their ships

bring you joy, and I hope that you will be able to see them very frequently. I

know that if our men realized that they were being watched and admired by such

a fine little patriot and loyal friend it would be a source of inspiration to

them and an additional incentive to do good work.

3. I don’t believe that it will be possible to have them

land in your mother’s field if it is cultivated, for you know that ships must

have a perfectly level, clear field in which to land successfully. Besides, we

try very hard not to injure crops or anything else in the performance of our

duties, for the country needs all its resources very badly and the soldiers

must do everything in their power to conserve and increase them.

4. I am going to have one of our aviators drop this note

to you, and also a copy of the Payne Field Zoom, and I want to tell you that

both I and all the members of my command regard you as one of our true friends.

5. With five of your brothers in uniform, fighting for

their country, and you at home doing your bit in the best way you can, Uncle

Sam may well feel satisfied with the way the Dawson family has responded to the

call, and the fact that far and wide throughout the land all Americans are

rallying to the flag enables us all to look to the future with firm confidence

and great hope.

JACK W. HEARD,

Lieutenant Colonel, J.M.A, A.S.A, U.S. Army.

So far as we know, Colonel Heard kept his end of the

bargain and delivered the letter to Wardie Dawson and, presumably Wardie in

turn continued to enjoy the airships flying above his mother’s house in

Okolona, the cornfield intact. In time, of course, the “War to End All Wars”

ended and Payne Field closed. Today,

nothing remains of Payne Field, with the exception of a hanger which was

disassembled and sold to a company in nearby Tupelo. In 1934, the Gravlee

Lumber Company (left) moved to Tupelo from Nettleton and took over the building and

used the former hanger for storage. In 1945, Guy Justis Gravlee, Jr., returned

from World War II to take over the family business. Interestingly, Gravlee was

himself a decorated officer in the Army Air Corps, and was awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism and extraordinary achievement and the

Air Medal with Nine Oak Leaf Clusters for service in Europe. After the war, he

had a distinguished career with the Mississippi National Guard. In 1962,

Gravlee was in command of the National Guards troops dispatched by President

Kennedy in response to the rioting at Ole Miss* and commanded the National

Guard activities following Hurricane Camille in 1969. No doubt, Gravlee, as an

airman himself, appreciated the history of the former Payne Field hanger. Major

General Gravlee died after a lengthy illness in December, 2010.

So far as we know, Colonel Heard kept his end of the

bargain and delivered the letter to Wardie Dawson and, presumably Wardie in

turn continued to enjoy the airships flying above his mother’s house in

Okolona, the cornfield intact. In time, of course, the “War to End All Wars”

ended and Payne Field closed. Today,

nothing remains of Payne Field, with the exception of a hanger which was

disassembled and sold to a company in nearby Tupelo. In 1934, the Gravlee

Lumber Company (left) moved to Tupelo from Nettleton and took over the building and

used the former hanger for storage. In 1945, Guy Justis Gravlee, Jr., returned

from World War II to take over the family business. Interestingly, Gravlee was

himself a decorated officer in the Army Air Corps, and was awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism and extraordinary achievement and the

Air Medal with Nine Oak Leaf Clusters for service in Europe. After the war, he

had a distinguished career with the Mississippi National Guard. In 1962,

Gravlee was in command of the National Guards troops dispatched by President

Kennedy in response to the rioting at Ole Miss* and commanded the National

Guard activities following Hurricane Camille in 1969. No doubt, Gravlee, as an

airman himself, appreciated the history of the former Payne Field hanger. Major

General Gravlee died after a lengthy illness in December, 2010.

After Payne Field closed, Colonel Jack Heard moved on to

other fields of endeavor. After organizing the Flying Circus (the forerunner of

the Thunderbirds) in 1919, Heard went back to the cavalry and then transitioned

into mechanized cavalry, ultimately commanding the 5th Armored

Division. A man of varied interests, including coin and stamp collecting,

astronomy, rose culture, history and finance, he retired in 1946 as a Major

General and died at Brooke Army Hospital in 1976. Back in Okolona, Wardie G.

Dawson, the little boy who wrote the letter, died in 1961 at age 55 and is

buried in Okolona’s Oddfellow Cemetery near one of his brothers, Jesse Howard,

who served in WWI. According to an obituary published at the time of his death, Ward Dawson "held various odd jobs and was widely known for his thoroughness in distributing advertising material. He was a big booster for Okolona and met visitors and newcomers with cheerful greetings and [a] cordial welcome."

After Payne Field closed, Colonel Jack Heard moved on to

other fields of endeavor. After organizing the Flying Circus (the forerunner of

the Thunderbirds) in 1919, Heard went back to the cavalry and then transitioned

into mechanized cavalry, ultimately commanding the 5th Armored

Division. A man of varied interests, including coin and stamp collecting,

astronomy, rose culture, history and finance, he retired in 1946 as a Major

General and died at Brooke Army Hospital in 1976. Back in Okolona, Wardie G.

Dawson, the little boy who wrote the letter, died in 1961 at age 55 and is

buried in Okolona’s Oddfellow Cemetery near one of his brothers, Jesse Howard,

who served in WWI. According to an obituary published at the time of his death, Ward Dawson "held various odd jobs and was widely known for his thoroughness in distributing advertising material. He was a big booster for Okolona and met visitors and newcomers with cheerful greetings and [a] cordial welcome."

* One of the

National Guardsmen dispatched to Ole Miss under Gravlee’s command was my

father-in-law, Rayford Williams of New Albany, Mississippi.

PHOTO AND IMAGE SOURCES:

(1) Curtiss JN-4: http://science.howstuffworks.com

(2) Col. Heard: http://earlyaviators.com

(3) Allen: http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com

(4) JN-4 painting: http://www.glennhcurtissmuseum.org

(5) Col. Heard 2: http://earlyaviators.com

(6) Gravlee Lumber Co.: http://www.loopnet.com

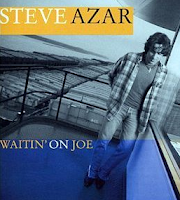

The

first legal liquor store in Mississippi following the end of prohibition opened

in Greenville on August 6, 1966. Located

on Highway 82, the “Jigger & Jug,” owned by the Azar brothers of Greenville,

was granted a liquor license from the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division on

Friday, July 29, 1966. While the license granted was actually the second issued

in Mississippi (the first was to the Broadwater Beach Resort in Biloxi), the “Jigger &

Jug” was the first self-serve package liquor store to open. The first shipment

of alcohol arrived at the store from the state warehouse in Jackson on

Wednesday morning following the granting of the license. The shipment included

186 cases of whiskey, wine, gin, vodka and liqueurs. The first case unloaded,

according to The Delta Democrat-Times,

was “Old Granddad” whiskey. A sidebar photograph next to the story (right) was titled

simply “Happy Day.” The “Jigger & Jug” is still in operation at the same

location, although ownership recently changed hands.

The

first legal liquor store in Mississippi following the end of prohibition opened

in Greenville on August 6, 1966. Located

on Highway 82, the “Jigger & Jug,” owned by the Azar brothers of Greenville,

was granted a liquor license from the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division on

Friday, July 29, 1966. While the license granted was actually the second issued

in Mississippi (the first was to the Broadwater Beach Resort in Biloxi), the “Jigger &

Jug” was the first self-serve package liquor store to open. The first shipment

of alcohol arrived at the store from the state warehouse in Jackson on

Wednesday morning following the granting of the license. The shipment included

186 cases of whiskey, wine, gin, vodka and liqueurs. The first case unloaded,

according to The Delta Democrat-Times,

was “Old Granddad” whiskey. A sidebar photograph next to the story (right) was titled

simply “Happy Day.” The “Jigger & Jug” is still in operation at the same

location, although ownership recently changed hands.  Stephen

Thomas Azar was born just two years before the liquor store opened. His father

was Joe Azar, one of the original owners of the “Jigger & Jug.” At age ten,

Steve Azar started writing songs and developing his talents as a guitar player.

Heavily influenced by blues artists in the Greenville area, the young singer first

learned about blues music behind his father’s liquor store. “I was hooked on

Eugene Powell (Sonny Boy Nelson) who made Blues records back in the 1930’s,”

writes Azar, “[and] would hang out behind my dad’s liquor store, sit on a crate and

listen to Eugene sing about his day and about his night before. Those were my

first lyric writing lessons, even though I didn’t know it at the time.”

Stephen

Thomas Azar was born just two years before the liquor store opened. His father

was Joe Azar, one of the original owners of the “Jigger & Jug.” At age ten,

Steve Azar started writing songs and developing his talents as a guitar player.

Heavily influenced by blues artists in the Greenville area, the young singer first

learned about blues music behind his father’s liquor store. “I was hooked on

Eugene Powell (Sonny Boy Nelson) who made Blues records back in the 1930’s,”

writes Azar, “[and] would hang out behind my dad’s liquor store, sit on a crate and

listen to Eugene sing about his day and about his night before. Those were my

first lyric writing lessons, even though I didn’t know it at the time.”  Azar had

his first Nashville recording session at age fourteen. After attending Delta

State University, he moved to Nashville in 1993 to pursue a career in music.

During his career, he has toured with Bob Seger, Carrie Underwood, Reba

McIntire, Tim McGraw, Hootie and the Blowfish and Montogomery Gentry. In 2002,

Mississippi native Morgan Freeman appeared in a video of Azar’s song “Waitin’

on Joe.” Since then, Azar has focused on his Mississippi roots and developed a

sound he calls “Delta Soul.” He continues to tour and record on his own label,

Ride Records. He is scheduled to perform at the Mississippi Agricultural Museum

in Jackson for a benefit concert on October 13, 2012.

Azar had

his first Nashville recording session at age fourteen. After attending Delta

State University, he moved to Nashville in 1993 to pursue a career in music.

During his career, he has toured with Bob Seger, Carrie Underwood, Reba

McIntire, Tim McGraw, Hootie and the Blowfish and Montogomery Gentry. In 2002,

Mississippi native Morgan Freeman appeared in a video of Azar’s song “Waitin’

on Joe.” Since then, Azar has focused on his Mississippi roots and developed a

sound he calls “Delta Soul.” He continues to tour and record on his own label,

Ride Records. He is scheduled to perform at the Mississippi Agricultural Museum

in Jackson for a benefit concert on October 13, 2012.