Before

moving to the attack, Ross sent a letter under a flag of truce to Colonel

Coates. In it, he claimed that two men from the 6th Texas Cavalry had been

executed by members of a black regiment near Mechanicsburg. “From threats made

by officers and men of your command during their recent raids through this

country,” Ross wrote, “I am led to infer that yourself and command indorse the

cold-blooded and inhumane proceedings.” Ross stated that if the same fate would

befall all Confederates who might hereafter be captured, then he was “prepared

to accept the terms, and will know what course henceforth to pursue…” In

answer, Coates assured Ross that, if true, “this type of warfare and treatment

of prisoners is as sincerely deprecated by me as by yourself.” However, Coates

also took the Confederate to task for the same outrages. In the recent fighting

at Liverpool, Coates claimed that nineteen of the black soldiers had been

captured. Of these, six had since been found dead, “presenting every appearance

of having been brutally used, and compelling me to arrive at the conclusion

that they had been murdered after having been taken prisoner.” While Ross was to

some extent stalling for time in order for Richardson’s men to arrive (which

they did the same day), the issue of the treatment of prisoners, especially African

American soldiers who were not regarded as legitimate by the Confederate

government, was a serious matter. In his after action report, Ross stated that

he “would not recognize negroes as soldiers or guaranty them nor their officers

protection as such.”

Before

moving to the attack, Ross sent a letter under a flag of truce to Colonel

Coates. In it, he claimed that two men from the 6th Texas Cavalry had been

executed by members of a black regiment near Mechanicsburg. “From threats made

by officers and men of your command during their recent raids through this

country,” Ross wrote, “I am led to infer that yourself and command indorse the

cold-blooded and inhumane proceedings.” Ross stated that if the same fate would

befall all Confederates who might hereafter be captured, then he was “prepared

to accept the terms, and will know what course henceforth to pursue…” In

answer, Coates assured Ross that, if true, “this type of warfare and treatment

of prisoners is as sincerely deprecated by me as by yourself.” However, Coates

also took the Confederate to task for the same outrages. In the recent fighting

at Liverpool, Coates claimed that nineteen of the black soldiers had been

captured. Of these, six had since been found dead, “presenting every appearance

of having been brutally used, and compelling me to arrive at the conclusion

that they had been murdered after having been taken prisoner.” While Ross was to

some extent stalling for time in order for Richardson’s men to arrive (which

they did the same day), the issue of the treatment of prisoners, especially African

American soldiers who were not regarded as legitimate by the Confederate

government, was a serious matter. In his after action report, Ross stated that

he “would not recognize negroes as soldiers or guaranty them nor their officers

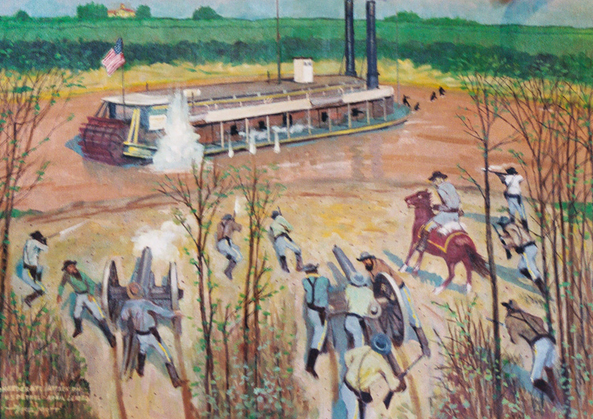

protection as such.”  Saturday,

March 5, 1864, was a clear and cool day. Keeping watch over Yazoo City from

their anchor below the town was the fleet of Union vessels, now under the

command of Thomas McElroy of the Petrel

(Commander Owen had since returned to Vicksburg). McElroy had been asked to

support the infantry with the fleet’s artillery. At 10:25, a watchman on the Marmora reported that the Confederates

were advancing in force and promptly opened fire. Ross and Richardson were,

indeed, advancing. Leaving their camps at 8:00 am, the nearly 2,000 cavalrymen

thundered down the Benton Plank Road toward Yazoo City. Ross instructed the 3rd

Texas Cavalry to attack the main fort on the Benton Road, while the 9th Texas,

under Dudley Jones, and the 27th Texas, under Col. Edwin R. Hawkins, would

handle the two smaller forts on either side of Redoubt McKee. Richardson’s Tennesseans,

along with the 6th Texas and Thrall’s Battery, veered off to the right on a

connecting road that intersected the Lexington Road.

Saturday,

March 5, 1864, was a clear and cool day. Keeping watch over Yazoo City from

their anchor below the town was the fleet of Union vessels, now under the

command of Thomas McElroy of the Petrel

(Commander Owen had since returned to Vicksburg). McElroy had been asked to

support the infantry with the fleet’s artillery. At 10:25, a watchman on the Marmora reported that the Confederates

were advancing in force and promptly opened fire. Ross and Richardson were,

indeed, advancing. Leaving their camps at 8:00 am, the nearly 2,000 cavalrymen

thundered down the Benton Plank Road toward Yazoo City. Ross instructed the 3rd

Texas Cavalry to attack the main fort on the Benton Road, while the 9th Texas,

under Dudley Jones, and the 27th Texas, under Col. Edwin R. Hawkins, would

handle the two smaller forts on either side of Redoubt McKee. Richardson’s Tennesseans,

along with the 6th Texas and Thrall’s Battery, veered off to the right on a

connecting road that intersected the Lexington Road.  Richardson’s

men quickly overwhelmed the two companies manning the Lexington Road position.

When news of the attack reached Coates, he ordered four companies of the 8th Louisiana

(A.D.) posted in town to double-quick to the support of the heavily outnumbered

cavalrymen, but it was too late. Major McKee also dispatched a company from the

11th Illinois to support the collapsing right flank. The reinforcements, such

as they were, were swept into town, with the Tennesseans in hot pursuit. In a

matter of minutes, the Lexington Road had been opened into Yazoo City.

Confederate artillery fire concentrated on Redoubt McKee and prevented any more

reinforcements from reaching the Lexington Road. Ross’ other troops also

quickly captured the other smaller forts to the left, and Redoubt McKee was

quickly surrounded on three sides. In just thirty minutes, the Confederates

were in possession of the town (seen below, in a post-war view), except for a row of buildings fronting the

river, which were protected by naval fire.

Richardson’s

men quickly overwhelmed the two companies manning the Lexington Road position.

When news of the attack reached Coates, he ordered four companies of the 8th Louisiana

(A.D.) posted in town to double-quick to the support of the heavily outnumbered

cavalrymen, but it was too late. Major McKee also dispatched a company from the

11th Illinois to support the collapsing right flank. The reinforcements, such

as they were, were swept into town, with the Tennesseans in hot pursuit. In a

matter of minutes, the Lexington Road had been opened into Yazoo City.

Confederate artillery fire concentrated on Redoubt McKee and prevented any more

reinforcements from reaching the Lexington Road. Ross’ other troops also

quickly captured the other smaller forts to the left, and Redoubt McKee was

quickly surrounded on three sides. In just thirty minutes, the Confederates

were in possession of the town (seen below, in a post-war view), except for a row of buildings fronting the

river, which were protected by naval fire.  The battered remnants of Coates’

troops in town, including the colonel himself, took up firing positions in

the buildings along the river and fighting soon became a house-to-house affair. According to

Orton Ingersoll of the 11th Illinois, however, Colonel Coates was in

the street “giving orders as cool as though nothing unusual was going on. The

bullets were flying around him as thick as hail.” With

his command virtually surrounded, Major McKee sent a ten-man party into town to

ask for help. Only three made it. Coates was informed that the fort’s only gun, a 12-pound howitzer, had been disabled. Coates requested by

courier that the Marmora send another

12-pound howitzer. In just seven minutes, the Marmora steamed to the landing and unloaded another howitzer and

gun crew. Before they could move the gun to the relief of the redoubt, however,

charging Confederates surrounded the gun. Ensign Shepley Holmes, who had been

sent ashore in charge of the gun, fled back to the gunboat; McElroy refused to

let him aboard. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew stayed by their gun until it too was disabled. All three, including Bartlett Laffey, a native of County Galway, Ireland, were awarded Medals of Honor for their bravery under fire. All three would later have U.S. Navy ships named in their honor; the first USS Laffey, a Benson class destoryer, was lost during the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. In the confused fighting, men from the 8th Louisiana Infantry (A.D.) retook the naval howitzer.

The battered remnants of Coates’

troops in town, including the colonel himself, took up firing positions in

the buildings along the river and fighting soon became a house-to-house affair. According to

Orton Ingersoll of the 11th Illinois, however, Colonel Coates was in

the street “giving orders as cool as though nothing unusual was going on. The

bullets were flying around him as thick as hail.” With

his command virtually surrounded, Major McKee sent a ten-man party into town to

ask for help. Only three made it. Coates was informed that the fort’s only gun, a 12-pound howitzer, had been disabled. Coates requested by

courier that the Marmora send another

12-pound howitzer. In just seven minutes, the Marmora steamed to the landing and unloaded another howitzer and

gun crew. Before they could move the gun to the relief of the redoubt, however,

charging Confederates surrounded the gun. Ensign Shepley Holmes, who had been

sent ashore in charge of the gun, fled back to the gunboat; McElroy refused to

let him aboard. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew stayed by their gun until it too was disabled. All three, including Bartlett Laffey, a native of County Galway, Ireland, were awarded Medals of Honor for their bravery under fire. All three would later have U.S. Navy ships named in their honor; the first USS Laffey, a Benson class destoryer, was lost during the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. In the confused fighting, men from the 8th Louisiana Infantry (A.D.) retook the naval howitzer.  To

the east, the fight for Redoubt McKee continued. Because of the steep

embankments, the Texans and Tennesseans arrayed on three sides of the

fortification had difficulty advancing, but the defenders, too few in number

and almost surrounded, could not break out. About noon, after four hours of

stalemate, Ross sent the commander of the fort, under a flag of truce, a demand

for his unconditional surrender. Ross, through a spokesman, reminded McKee that

in case the Confederates had to storm the works, he would be “unable to

restrain his men.” McKee’s answer was defiant. “I have no idea of

surrendering,” he said, and stated that Ross’ threat in regard to the treatment

of prisoners should have been in writing for all to see. Again demanding

surrender, Ross stated that he regretted “for the sake of humanity that you do

not find it consistent with your feelings of duty to your government to

surrender the redoubt, which I can certainly storm and take. As to the

treatment of prisoners,” Ross said, “I will try and have them protected…but you

may expect much bloodshed.” This no-holds policy did not set well with all of

Ross’ Confederates, however. A trooper in the 3rd Texas recalled that “the news

got out that Ross would Show no Quarter to prisoners…This caused a great deal

of dissatisfaction among our boys.” He concluded by saying “damned if I don’t

leave if this prisoner killing is not stoped.”

To

the east, the fight for Redoubt McKee continued. Because of the steep

embankments, the Texans and Tennesseans arrayed on three sides of the

fortification had difficulty advancing, but the defenders, too few in number

and almost surrounded, could not break out. About noon, after four hours of

stalemate, Ross sent the commander of the fort, under a flag of truce, a demand

for his unconditional surrender. Ross, through a spokesman, reminded McKee that

in case the Confederates had to storm the works, he would be “unable to

restrain his men.” McKee’s answer was defiant. “I have no idea of

surrendering,” he said, and stated that Ross’ threat in regard to the treatment

of prisoners should have been in writing for all to see. Again demanding

surrender, Ross stated that he regretted “for the sake of humanity that you do

not find it consistent with your feelings of duty to your government to

surrender the redoubt, which I can certainly storm and take. As to the

treatment of prisoners,” Ross said, “I will try and have them protected…but you

may expect much bloodshed.” This no-holds policy did not set well with all of

Ross’ Confederates, however. A trooper in the 3rd Texas recalled that “the news

got out that Ross would Show no Quarter to prisoners…This caused a great deal

of dissatisfaction among our boys.” He concluded by saying “damned if I don’t

leave if this prisoner killing is not stoped.”

The

attack and the threatened slaughter of prisoners never came, however. Sometime

after 2:00 in the afternoon, Richardson’s men began withdrawing from the town

and Ross’ men pulled back from the fort. The reason, they later explained, was

that after considering a charge on the redoubt, they concluded that the results

would not be worth the casualties. Plus, the Confederates received word that Union

reinforcements were then steaming upriver. This was true, although the 10th

Louisiana Infantry (A.D.) did not arrive until late that night. The

Confederates were also running low on ammunition.

Coates

provided a completely different explanation for the reversal of fortunes,

however. According to the Union commander, the remnants of his command “made a

desperate charge through the streets completely routing the Confederates and pursuing

them entirely through town.” Seeing their right flank falling back, the

Confederates around the fort also “began to retreat in great disorder,”

according to Coates. He even asserted that Major McKee and just six men sallied

forth from the works and routed an entire Confederate regiment. Acting Master

Thomas Gibson, stationed aboard the U.S.S. Marmora,

offered another reason for the turning of the tide. “In the engagement at Yazoo

City,” he wrote, “a 12-pounder howitzer, one of the broadside guns of this

vessel, was landed and mounted on a field carriage and used in the heat of the

engagement in the streets of the city, and to the bravery of that gun's crew

may be attributed the change of the fortune of the day. Our land forces were

being steadily driven back on the river until this gun was landed and brought

to bear on the position of the enemy, driving them from the streets and houses

to the hills, where our broadsides could play on them. The carriage of the gun

was badly cut by rifle bullets and rammer nearly cut in two by the same, mutely

testifying to the severity of the fire to which the men were exposed.” While the

navy deserves some credit for holding Richardson’s men at bay in the town,

Coates’ claims lack any credibility. Regardless, the Federals retained possession

of Yazoo City and had survived the attack, if barely.

They

did not stay long. Coates received orders from Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson the

next day to embark his entire force and return to Vicksburg. By the evening of

the 6th, Yazoo City was no longer under Union occupation. Ross and Richardson returned

to their camp to rest and refit, but reentered the town once the Federals

departed. While there, so many of Ross’ threadbare and hungry Texans “loaded

themselves with plunder” taken from the citizens of Yazoo City that the general

had to remind his troops that horses, mules and other valuables belonged to the

people of Yazoo City and threatened to treat as common criminals any soldiers

caught in possession of the same. Soon after the battle, Ross also had to deal

with a mutiny among the men of the 6th Texas who threatened to kill an

unpopular officer.

On

paper, the Yazoo City Expedition accomplished very little. The campaign had

almost no effect on Sherman’s Meridian Expedition. After all, Ross’ Texas

brigade nipped at Sherman’s flanks for a full twenty days before returning to

Yazoo City. A great deal of cotton was taken by the Federal fleet, which

accounted for a great deal of money, and it can perhaps be said that the

planters along the Yazoo learned the hard lessons of war. Certainly, the navy

did its part, navigating through the twisting bends of the upper Yazoo and

dodging the wrecks of steamers along the way. One of the fleet’s gunboats would

herself become a wreck just two months later. Attacked once again at Yazoo City

during an ill-advised venture, the Petrel

(right) was captured by Confederate cavalry, burned to the waterline and her eight

24-pound rifled cannon removed and sent to Mobile. [For more on the story of the Petrel, see: http://andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2012/11/the-capture-of-uss-petrel.html] While the Yazoo expedition

accomplished little, the viciousness of the fighting and the threats and

counter-threats regarding the treatment of prisoners, especially the black

troops, would more and more become the norm in Mississippi in 1864 and 1865. Interestingly,

the battle of Yazoo City stands as one of the few battles in Mississippi where

the only Mississippians engaged were not only Union soldiers but were African

Americans, as the Confederate force was entirely made up of Texans and

Tennesseans.

On

paper, the Yazoo City Expedition accomplished very little. The campaign had

almost no effect on Sherman’s Meridian Expedition. After all, Ross’ Texas

brigade nipped at Sherman’s flanks for a full twenty days before returning to

Yazoo City. A great deal of cotton was taken by the Federal fleet, which

accounted for a great deal of money, and it can perhaps be said that the

planters along the Yazoo learned the hard lessons of war. Certainly, the navy

did its part, navigating through the twisting bends of the upper Yazoo and

dodging the wrecks of steamers along the way. One of the fleet’s gunboats would

herself become a wreck just two months later. Attacked once again at Yazoo City

during an ill-advised venture, the Petrel

(right) was captured by Confederate cavalry, burned to the waterline and her eight

24-pound rifled cannon removed and sent to Mobile. [For more on the story of the Petrel, see: http://andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2012/11/the-capture-of-uss-petrel.html] While the Yazoo expedition

accomplished little, the viciousness of the fighting and the threats and

counter-threats regarding the treatment of prisoners, especially the black

troops, would more and more become the norm in Mississippi in 1864 and 1865. Interestingly,

the battle of Yazoo City stands as one of the few battles in Mississippi where

the only Mississippians engaged were not only Union soldiers but were African

Americans, as the Confederate force was entirely made up of Texans and

Tennesseans.

As

a follow-up, it is interesting to note what happened to some of the men

engaged. Incredibly, two of the principal Federal officers at Yazoo City

remained in Mississippi after the war. Embury D. Osband, in command of the 1st

Mississippi Cavalry, A.D., and later in command of a brigade of black troops,

moved to Yazoo County and engaged in the cotton business there until his death

from diphtheria on October 4, 1866, at the age of 34. Buried in Vicksburg, he

is the highest ranking officer interred in the Vicksburg National Military

Park. Meanwhile, George McKee, who challenged Sul Ross from the redoubt, became

a lawyer in Vicksburg and served four terms in Congress as a Republican from

Mississippi. After Reconstruction ended, McKee remained in Mississippi and served

as postmaster in Jackson in the late 1880s. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery

in Jackson. Colonel Coates, despite his less-than-stellar defense of Yazoo City, was

brevetted as a brigadier general on March 13, 1865 for

"faithful and meritorious services." After the war, he was a grain

merchant. Coates died in 1902 and is buried at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in Missouri (above).

On the Confederate side, Sul Ross (right) went on to become an influential

Texas politician, serving two terms as governor and also as president of Texas

A&M. Sul Ross State University is named in his honor. Robert V. Richardson,

who at one point had been relieved of command by his pre-war business partner

Nathan Bedford Forrest, would lose his West Tennessee brigade soon after the

Yazoo Expedition. After the war, the apparently unpopular Richardson entered

the railroad business in Memphis. Several years later, while on a business to

Missouri, Richardson was killed by an unknown assailant in a tavern.

On the Confederate side, Sul Ross (right) went on to become an influential

Texas politician, serving two terms as governor and also as president of Texas

A&M. Sul Ross State University is named in his honor. Robert V. Richardson,

who at one point had been relieved of command by his pre-war business partner

Nathan Bedford Forrest, would lose his West Tennessee brigade soon after the

Yazoo Expedition. After the war, the apparently unpopular Richardson entered

the railroad business in Memphis. Several years later, while on a business to

Missouri, Richardson was killed by an unknown assailant in a tavern.

On the Confederate side, Sul Ross (right) went on to become an influential

Texas politician, serving two terms as governor and also as president of Texas

A&M. Sul Ross State University is named in his honor. Robert V. Richardson,

who at one point had been relieved of command by his pre-war business partner

Nathan Bedford Forrest, would lose his West Tennessee brigade soon after the

Yazoo Expedition. After the war, the apparently unpopular Richardson entered

the railroad business in Memphis. Several years later, while on a business to

Missouri, Richardson was killed by an unknown assailant in a tavern.

On the Confederate side, Sul Ross (right) went on to become an influential

Texas politician, serving two terms as governor and also as president of Texas

A&M. Sul Ross State University is named in his honor. Robert V. Richardson,

who at one point had been relieved of command by his pre-war business partner

Nathan Bedford Forrest, would lose his West Tennessee brigade soon after the

Yazoo Expedition. After the war, the apparently unpopular Richardson entered

the railroad business in Memphis. Several years later, while on a business to

Missouri, Richardson was killed by an unknown assailant in a tavern.

As for the common soldiers on both sides,

black and white, who fought in the small but brutal battles of Liverpool and

Yazoo City, the war would continue for another gruesome year and then some. For

approximately seventy men, however, the fierce struggles on the banks of the

Yazoo in the winter of 1864 would be their last.

* For the story of the Yazoo Expedition to this point, please see part one of this article: http://andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2014/03/no-quarter-asked-or-given-yazoo.html

PHOTO AND IMAGE SOURCES:

(1) USCT soldier: http://www.lwfaaf.net

(2) 6th Texas Flag: https://www.tsl.texas.gov

(3) Fighting: http://www.politico.com

(4) Yazoo City http://visityazoo.org

(5) Flag of the 11th Illinois: http://www.civil-war.com

(6) 12-pound howitzer: http://www.history.navy.mil

(7) USS Petrel: http://www.logarchism.com

(8) Coates: http://www.findagrave.com

(9) Ross: http://en.wikipedia.org

* For the story of the Yazoo Expedition to this point, please see part one of this article: http://andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2014/03/no-quarter-asked-or-given-yazoo.html

PHOTO AND IMAGE SOURCES:

(1) USCT soldier: http://www.lwfaaf.net

(2) 6th Texas Flag: https://www.tsl.texas.gov

(3) Fighting: http://www.politico.com

(4) Yazoo City http://visityazoo.org

(5) Flag of the 11th Illinois: http://www.civil-war.com

(6) 12-pound howitzer: http://www.history.navy.mil

(7) USS Petrel: http://www.logarchism.com

(8) Coates: http://www.findagrave.com

(9) Ross: http://en.wikipedia.org

No comments:

Post a Comment